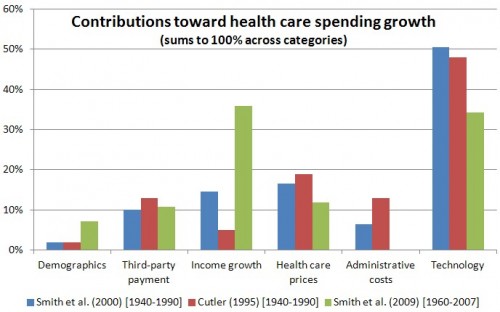

As I posted previously, many studies have pointed to technology as a principal driver of health care spending growth. Those studies also credit third party payment (i.e., insurance) and income for some of the blame too. More interesting, coverage, income, and technology interact; their intersection is explored in a few papers summarized below.

The 2009 paper in Health Affairs by Shelia Smith, Joseph Newhouse, and Mark Freeland is one of the sources for the chart above. (See this post for additional detail.) In it, the authors note that "interrelationships among technology, income, and insurance are strong," which makes "it difficult to assign specific quantitative magnitudes to each factor."

There's an obvious way in which insurance and income interact with health care technology: they broaden financial access to it. Income does so directly. The more money you have the more you can buy. Insurance does so by spreading technology's cost across individuals, not all of whom require access to the same types and amount of it at the same time (or in the same year). Insurance has an income effect.

There's a more subtle way insurance and income interact with technology. Smith et al. put their finger on it. "[T]he rate of technological innovation is influenced by the size of the market, which in turn is influenced by income and insurance." The size of the market is influenced by insurance in three ways: (1) The absolute or relative size of the population covered, (2) the level of coverage insured people tend to have, and (3) the manner in which insurers (public or private) pay providers.

Burton Weisbrod's fascinating 1991 paper, "The Health Care Quadrilemma," may have been the first to deeply contemplate the insurance-technology nexus. In it, he explained "how the expansion of health insurance has paid for the development of cost-increasing technologies, and how the new technologies have expanded demand for insurance." Weisbrod recognized that the key linkage is the research and development (R&D) process:

(1) The amount of resources going into the R&D process, and its direction, during some time interval, depend in part on the mechanisms expected to be used to finance the provision of health care in future periods, when the fruits of the research process become marketable. This is simply to say that R&D is influenced by expected utilization, which depends on the insurance system. Reciprocally, (2) the demand for health care insurance depends, in part, on the state of technology, which reflects R&D in prior periods. These relationships help to explain why (3) long-run growth of health care expenditures is a by-product of the interaction of the R&D process with the health care insurance system.

Though I want to focus principally on how insurance affects R&D, Weisbrod also discussed the reverse direction: how R&D affects insurance. For example, he pointed to advances in fertilization technology that increased demand for coverage of it. In 1988, five states mandated coverage of certain fertilization technology. Just one year later, that number was up to nine; today it's 15. More generally, Weisbrod argued that health care technology that increases the mean and variance of health care expenditures tend to increase demand for insurance.

Coverage affects R&D by changing how providers are paid. Pressures to contain cost, as codified by new payment systems (e.g., bundled payments, ACOs) can affect R&D by shaping the medical market differently from prior payment systems. Retrospective payment, Weisbrod argues, sends the message, "Develop new technologies that enhance the quality of care, regardless of the effects on cost." Prospective (whether bundled or capitated, though to different degrees) payment sends the message, "Develop new technologies that reduce costs, provided that quality does not suffer too much." (Italics original in both cases.)

Note that cost reduction in the latter case is from the perspective of the provider, not society. The sense of cost reduction pressure is different under bundled payments (lower per episode costs, but not fewer episodes) than under annual capitation (lower overall costs, but only within the year). As the CBO pointed out, "Even when technological innovation leads to a decline in the cost of a given service, net spending rises if the use of services increases sufficiently."

Examples of how coverage and payment shaped technology can be found in a number of studies, including Weisbrod's:

- When Medicare dialysis reimbursement was capped, newly developed equipment cut session time in half, saving labor costs (Weisbrod).

- When chochlear implants became less profitable after "application of the DRG-pricing system [t]he 3M Company, the manufacturer of the first FDA-approved single-channel cochlear implant model, halted research" on a more advanced model (Weisbrod).

- Prospective pricing has increased the expected profitability of drugs that can substitute for more costly treatments (e.g., beta blockers instead of coronary bypass surgery and cimetidine instead of ulcer surgery) (Weisbrod).

- Policies by the CDC and Medicare in the early 1990s that increased coverage and use of certain vaccines, and a vaccine injury fund introduced in 1986 that protected manufacturers from lawsuits, encouraged 2.5 times more new vaccine clinical trials per year for each affected disease (Finkelstein).

- The introduction of Medicare and Medicaid are associated with 40-50% more US-based medical equipment patenting, relative to other US patenting and foreign medical equipment patenting (Clemens).

- Implementation of Medicare's drug benefit is associated with increases in preclinical testing and clinical trials for drug classes most likely affected by the policy (Blume-Kohout and Sood).

- Lower reimbursement by Medicaid programs for the care of pregnant women is associated with slower NICU adoption (Freedman, Lin, and Simon).

The basic point is the size of the market for technology with different characteristics is influenced by coverage. And, as Daron Acemoglu and Joshua Linn showed, market size matters. They exploited changing U.S. demographics (principally aging) to show that a 1% increase in a drug category's potential market size leads to a 6% increase in number of new drug entry in that category (4% brand and 2% generic). Their findings suggest that pharmaceutical R&D anticipates changes in market by 10-20 years, reflecting the time it takes to develop and bring a new drug to market.

Today, coverage is increasing, and changing in generosity. Payment systems are in flux. Though the existing research is hardly rich enough to permit us to make precise predictions about what these changes will do, we can be confident they are shaping the future of health care technology.

(See also related, largely theoretical, work by Garber, Jones, and Romer and Baumgardner.)

Austin B. Frakt, PhD, is a health economist with the Department of Veterans Affairs and an associate professor at Boston University’s School of Medicine and School of Public Health. He blogs about health economics and policy at The Incidental Economist and tweets at @afrakt. The views expressed in this post are that of the author and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Department of Veterans Affairs or Boston University.